6. The age of Reformations

Reforming the Church became a relatively commonplace idea since the end of the first millennium (see page 4 of this module), resting on the desire to return to a state considered original. Reformation, a term that encompasses all Protestant reforms, and which also influenced a Catholic reformation (also called Counter-Reformation), differed from earlier movements by its extent and the fact that it changed the face of Europe.

Reformation should be placed in its long-run historical context. Time and again since the Middle-Ages, the Latin Church initiated reforms aimed at rectifying practices that were deemed to be in error, in order to return to the purity of the original Church. The Gregorian Reform (11th century) is the most widely known, though it was not the only one, by far. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Western Church was in crisis: it was divided by the Great Schism (1378-1417), and faced the critical of the theologian John Wycliffe and the priest Jan Hus Prague, who criticized the wealth of the Church and its cumbersome hierarchy, and the vernacular instead of Latin. Renaissance Humanism appeared at the same time Historical criticism surfaced with humanism, and brought to the fore older and better textual versions of original works, including the Bible. Many humanists called for a reform of the Church, which the latter found difficult to attempt. Protestant Reformation took hold in this current, while gaining support at the political level.

.

Martin Luther, The Ninety-Five Theses

The 95 theses, which were said to have been posted on the door of the Church of Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, are considered the starting point of the Protestant Reformation. Luther condemned the indulgences, but without hostility towards the Pope. The theses nevertheless sparked off an upheaval.

“Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and ordinary lecturer therein at Wittenberg, intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them in that place. Therefore he asks that those who cannot be present and dispute with him orally shall do so in their absence by letter. In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Amen.

1. When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ``Repent'' (Mt 4:17), he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

2. This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

3. Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortification of the flesh […].

5. The pope neither desires nor is able to remit any penalties except those imposed by his own authority or that of the canons.

6. The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring and showing that it has been remitted by God; or, to be sure, by remitting guilt in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in these cases were disregarded, the guilt would certainly remain unforgiven […].

20. Therefore the pope, when he uses the words “plenary remission of all penalties,'' does not actually mean ``all penalties,'' but only those imposed by himself […].

21. Thus those indulgence preachers are in error who say that a man is absolved from every penalty and saved by papal indulgences.

22. As a matter of fact, the pope remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to canon law, they should have paid in this life.

23. If remission of all penalties whatsoever could be granted to anyone at all, certainly it would be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to very few […].

27. They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory […].

28. It is certain that when money clinks in the money chest, greed and avarice can be increased; but when the church intercedes, the result is in the hands of God alone […].

32. Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

33. Men must especially be on guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to him.

34. For the graces of indulgences are concerned only with the penalties of sacramental satisfaction established by man.

35. They who teach that contrition is not necessary on the part of those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessional privileges preach unchristian doctrine.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

38. Nevertheless, papal remission and blessing are by no means to be disregarded, for they are, as I have said (Thesis 6), the proclamation of the divine remission […].

48. Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting indulgences, needs and thus desires their devout prayer more than their money.”

Martin Luther, The Ninety-Five Theses (1517). http://www.luther.de/en/95thesen.html

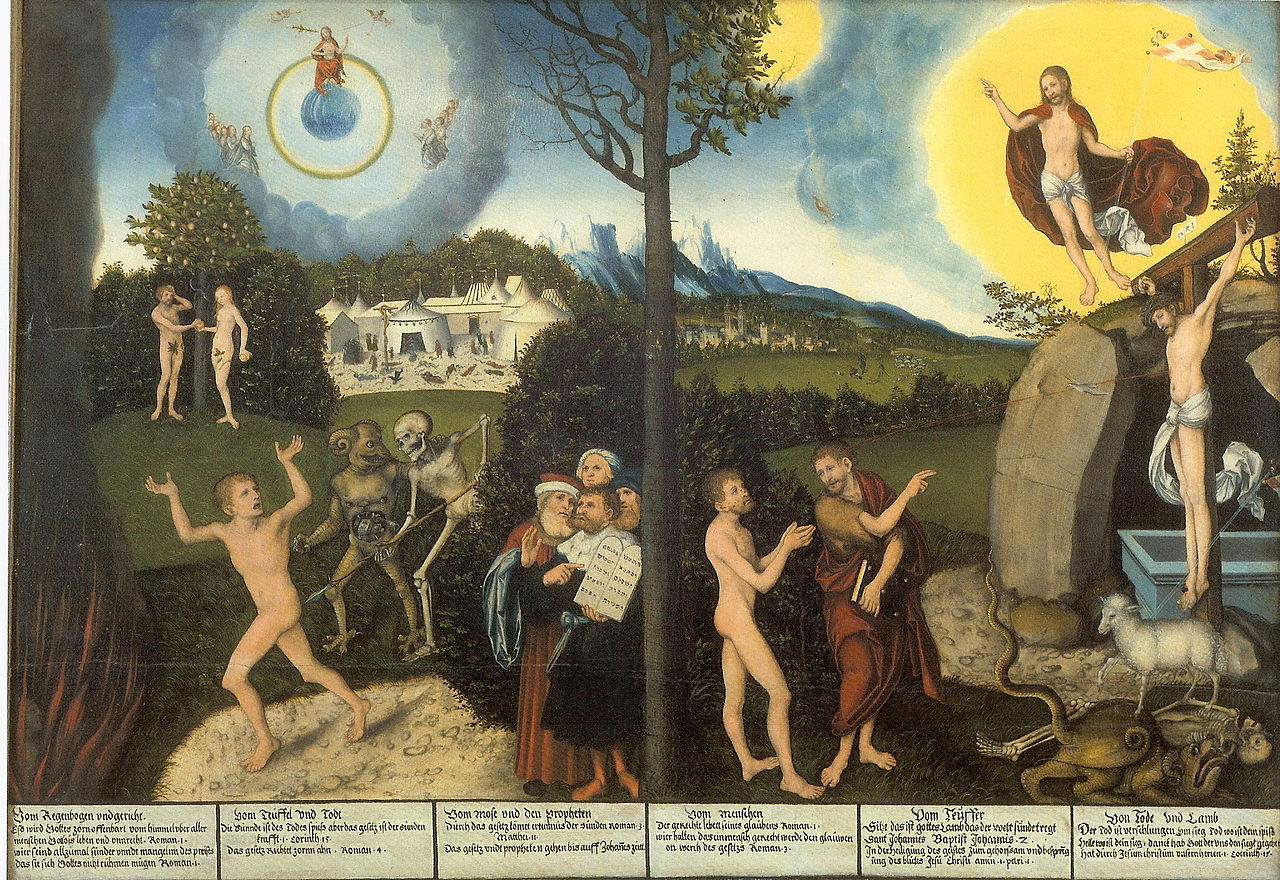

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Law and Grace

Lucas Cranach the Elder (c. 1472-1553) was a German painter. He had a career as a portrait artist and painted many portraits of Martin Luther and his family. Another part of his work was devoted to religious subjects. The Law and Grace contrasts the Law (i.e., the Old Testament), which condemns the sinner, and Grace (the Gospel), which saves him. This work is also related to the controversy between Catholics and Protestants: Catholics insist on Salvation through good deeds, while for Protestants, faith alone saves

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Law and Grace (1529). Gotha, Schlossmuseum Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cranach_Gesetz_und_Gnade_Gotha.jpg

Martin Luther, Concerning Christian Liberty.

Concerning Christian Liberty is one of the most important works of Luther, as it presents his thesis opposing good deeds, useless for salvation, and faith, the sole way to salvation.

“Let us examine the subject on a deeper and less simple principle. Man is composed of a twofold nature, a spiritual and a bodily. As regards the spiritual nature, which they name the soul, he is called the spiritual, inward, new man; as regards the bodily nature, which they name the flesh, he is called the fleshly, outward, old man. The Apostle speaks of this: “Though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day” (2 Cor. iv. 16). The result of this diversity is that in the Scriptures opposing statements are made concerning the same man, the fact being that in the same man these two men are opposed to one another; the flesh lusting against the spirit, and the spirit against the flesh (Gal. v. 17) […].One thing, and one alone, is necessary for life, justification, and Christian liberty; and that is the most holy word of God, the Gospel of Christ […].Meanwhile it is to be noted that the whole Scripture of God is divided into two parts: precepts and promises […].Now when a man has through the precepts been taught his own impotence, and become anxious by what means he may satisfy the law—for the law must be satisfied, so that no jot or tittle of it may pass away, otherwise he must be hopelessly condemned—then, being truly humbled and brought to nothing in his own eyes, he finds in himself no resource for justification and salvation. Then comes in that other part of Scripture, the promises of God […].For what is impossible for you by all the works of the law, which are many and yet useless, you shall fulfil in an easy and summary way through faith.”

Martin Luther, Concerning Christian Liberty. The Harvard Classics, vol. 36.

Council of Trent, Decree on Justification

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was an ecumenical council held in the Italian city of Trento. It was one of the most important councils of the Roman Catholic Church. In its proceedings, it condemned the Protestant reformers and implemented the means to combat their ideas by improving the Church’s ministry. The Council was the starting point of what has long been referred to as the Counter-Reformation, nowadays increasingly called the Catholic Reformation, as the issues which it set out to resolve also extended into the functioning of the Church.

Chapter 1: “[…] it is necessary that each one recognise and confess, that, whereas all men had lost their innocence in the prevarication of Adam-[…] they were so far the servants of sin […] although free will, attenuated as it was in its powers, and bent down, was by no means extinguished in them.”

Chapter 9: “But, although it is necessary to believe that sins are remitted […] gratuitously by the mercy of God for Christ's sake; yet […] [one cannot rely on the] certainty of the remission of his sins […].For even as no pious person ought to doubt of the mercy of God, of the merit of Christ, and of the virtue and efficacy of the sacraments […], no one can know […] that he has obtained the grace of God.”

Chapter 10: “Having, therefore, been thus justified, and made the friends and domestics of God, advancing from virtue to virtue, they are renewed, as the Apostle says, day by day; that is, by mortifying the members of their own flesh, and by presenting them as instruments of justice unto sanctification, they, through the observance of the commandments of God and of the Church, faith co-operating with good works, increase in that justice which they have received through the grace of Christ, and are still further justified […]. Do you see that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only.”

Council of Trent, Decree on Justification, 6th session (January 13, 1547). Trans. J. Waterworth.