1. What is Philosophy of Religion?

Philosophy of Religion

The encounter between philosophy and theology in the West European Middle Ages gave rise to discussions still going on today. Discussions about the relationship between faith and knowledge, about the question why God, if omnipotent and absolutely good, can still allow evil in the world, and about the possibility of free will if God predetermines everything.

These questions, primarily originating from the monotheist religions in the West, belong to what might be called traditional themes in philosophy of religion. Other traditional forms of philosophy of religion are philosophers' thinking about religion in general. Prominent historical examples include the theories of David Hume (1711-1767) on the origin and purpose of religion; Immanuel Kant’s (1724-1804) arguments that religious propositions are beyond proof; and Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844-1900) view of religion as a powerful tool for the weak and a “comforting illusion” meant as a cover up for the chaos of naked reality.

More recent philosophical discussions on religion have been inspired by e.g. philosophical language theories. While that has led to reflections on meaning and truth in terms of religious language, reflections within political philosophy concerns religion in the public space and minority rights. In addition, the philosophy of science has raised questions about the relationship between religion and science, and the central debates about theory and method in the study of religions can be illuminated by philosophical considerations.

In contrast to the empirical study of religions, philosophy of religion also works with so-called normative questions on the possible truth and value of various religions. It might thus also discuss whether the ritual slaughter of animals is morally acceptable, or whether the law of karma may be true when it says that the individual’s actions determine what will happen to that individual later in life.

The methods and objectives of philosophy of religion

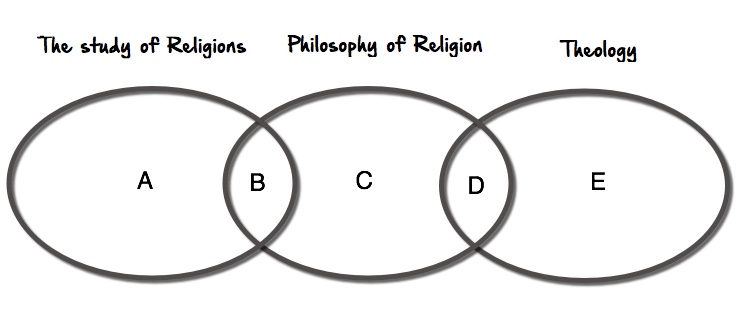

Philosophy of religion stands out from other approaches to religion, such as sociology or history of religion, because its methods are not primarily empirical. Instead, it consists of philosophical clarifications of concepts; of analyses and evaluation of arguments and assumptions; of theories about the relationship between religion and morality, or of what defines religion. However, as is the case with other study-of-religions approaches, the line between philosophy of religion and the empirical study of religions can be vague.

Characteristic of philosophy of religion is its interest in questions about the truth of religious theories and postulates and the moral value of religious practices. While other parts of the study of religions typically, and often with reference to methodological agnosticism, try to avoid being normative or prescriptive and do not consider e.g. whether the Hindu gods exist or not, or whether polygamy is morally good, philosophy of religion brings such themes up for discussion.

While, for example, a sociologist of religion might study the role of religion in the public space, a philosopher of religion is more likely to treat the question as whether there ought be religion at all in public space.

Theology is also interested in truth and value; subsequently some people find it difficult to distinguish between theology and philosophy of religion. However, in the case of e.g. questions like this: "Is it possible to prove the existence of God?", a difference is that while theology is usually expected to presuppose the truth and value of a particular religious tradition (typically Christian), a philosophical approach can be more fundamentally critical, and study several religious traditions.

Figure: The relationship between the study of religions, philosophy of religion and theology:

The text is a rewrite of an English draft version of an introduction to Horisont - a textbook for the Danish upper-secondary school RE, edited by Associate Professors Annika Hvithamar and Tim Jensen, and Upper-Secondary School teachers Allan Ahle and Lene Niebuhr, published by Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2013. The original introduction was written by Annika Hvithamar and Tim Jensen based on the contribution of C. Shaffalitzky de Muckadell

Philosophy of Religion: Normativity, faith and knowledge

Philosophy of religion can be normative. That means that it not only wishes to describe how something actually is, but also to assess its possible truth and value. Can the Law of Karma possibly be true? Is ritual slaughter morally acceptable? Is it possible to live a meaningful life as a member of the Catholic Church, or Scientology?

A common theme in classical philosophy of religion revolves around the relationship between faith and knowledge. The Danish philosopher, Soren Kierkegaard, (1813-1855) belongs to a philosophical tradition that rejects the idea that one can obtain knowledge of religious truths the same way as one acquires knowledge of historical matters. On the contrary, he felt that the more certain, objective knowledge one has of religious topics, the more this knowledge comes in the way of the main issue, that of faith. He sees faith as a subjective approach, a way of existing. Kierkegaard is therefore opposed to traditional theological attempts to prove God’s existence in different ways.

However, not everyone shares this view, and other philosophical religious system of thought refer to sources that are believed to justify them. When natural science theorizes the breakdown of the universe, it limits itself to empirical observations and experiments (and the theoretical constructions that can bind them together).

But how can religious thinking justify the expectation that the world will go under? Here it seems, additional sources must be referred to and used to make the claim plausible:

- Traditions claiming to be divine: one can argue that the expectation of the breakdown of the universe has been handed down traditionally (from myths or sacred texts) rather than acquired by human thinking.

- Reports of revelations or visions: one can argue that someone has obtained knowledge of the breakdown of the universe through supernatural channels (e.g. a revelation or a vision).

Normally, however, none of these sources of cognition and knowledge are considered reliable. Are we to believe that the world will break down tomorrow, just because it is claimed in an old myth, or because someone says he has had a 'vision'? If that was the argumentation in other contexts (i.e. the roof of the school will break down tomorrow) we would be quite skeptical. Moreover, we know that different traditions have conflicting myths and strange predictions. Thus, traditions and visions do not seem the most reliable path to knowledge.

Nevertheless, philosophers like William James (1842-1910) and William Alston (1921-2009) tried to argue that in principle nothing speaks against these roads to knowledge. It can be compared with the possibility of being clairvoyant. It might seem a bit unconvincing to argue that an old woman can predict the outcome of the local football club’s next match by looking in her crystal ball. But what if it turns out that she 'predicts' correctly 30 times in a row, will you not have to accept that she actually gains knowledge this way? In principle, it seems possible.

The text is a rewrite of an English draft version of an introduction to Horisont - a textbook for the Danish upper-secondary school RE, edited by Associate Professors Annika Hvithamar and Tim Jensen, and Upper-Secondary School teachers Allan Ahle and Lene Niebuhr, published by Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2013. The original introduction was written by Annika Hvithamar and Tim Jensen based on the contribution of C. Shaffalitzky de Muckadell