3. Die bedeutendsten muslimischen Feiertage

Bei der islamischen Zeitrechnung handelt es sich um einen Mondkalender, der aus 12 Monaten zu je 29 oder 30 Tagen besteht. Dieser Kalender zeichnet sich durch mehrere Besonderheiten aus: Unter anderem enthält er weder einen Schalttag noch einen Schaltmonat und auch der Monatsanfang ist am Lauf des Mondes orientiert, anstatt astronomischen Berechnungen zu folgen. Der Kalender wird von Muslimen benutzt, um den exakten Zeitpunkt der muslimischen Festtage zu bestimmen, insbesondere den Zeitpunkt des Fastens (Ramadan) und der Pilgerreise nach Mekka (Haddsch). In der muslimischen Welt werden auch historische Ereignisse auf Basis dieses Mondkalenders zeitlich verortet, wobei dies teilweise in Übereinstimmung mit dem gregorianischen Kalender erfolgt. Vier der Monate dieser Zeitrechnung sind heilig – während dieser Zeit ist es den Muslimen verboten, Sünden zu begehen oder Kriege zu führen; Kampfmaßnahmen gegen Ungläubige sind davon ausgenommen. Das erste Jahr der islamischen Zeitrechnung entspricht dem Jahr 662 christlicher Zeitrechnung und stimmt mit der Hidschra, das ist der Aufbruch Mohammeds von Mekka nach Medina, überein.

Mohammed verbietet den Nasī’. Nasī’

Diese Buchmalerei stellt einen Auszug aus dem Manuskript Buch der Hinterlassenschaften früherer Jahrhunderte (Kitāb al-āthār al-bāqiyah ‘an al-qurūn al-khāliyah) von Al-Biruni (973 – 1048) dar. Es handelt sich dabei um eine, im 17. Jahrhundert angefertigte Kopie einer Ausgabe aus dem 14. Jahrhundert. Das Buch enthält einen Vergleich verschiedener Kalender unterschiedlicher Zivilisationen und umfasst darüber hinaus zusätzliche Überlegungen zur Mathematik, Astronomie und Geschichte. Das Bild bezieht sich auf einen wichtigen Zeitpunkt für die Entwicklung der islamischen Zeitrechnung: Das Verbot des Nasī’.

French National Library (Bibliothèque nationale de France), MS Arabe 1489, folio 5 verso

Wikimedia Commons. Nutzung unter den Bedingungen der GNU-Lizenz für freie Dokumentation

Frei zugänglich. Bild online abrufbar unter URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maome.jpg

(30/03/2015)

Die Kritik des Nasī’

36 Gewiß, die Anzahl der Monate bei Allah ist zwölf Monate, im Buch Allahs (festgelegt) am Tag, da Er die Himmel und die Erde schuf. Davon sind vier geschützt. Das ist die richtige Religion. So fügt euch selbst in ihnen kein Unrecht zu. Und kämpft gegen die Götzendiener allesamt wie sie gegen euch allesamt kämpfen! Und wißt, daß Allah mit den Gottesfürchtigen ist!

37 Das Verschieben eines Monats ist nur eine Mehrung des Unglaubens. Damit werden diejenigen, die ungläubig sind, in die Irre geführt; sie erklären ihn in einem Jahr für ungeschützt und in einem (anderen) Jahr für geschützt, um der Anzahl dessen gleichzukommen, was Allah für geschützt erklärt hat; so erklären sie für ungeschützt, was Allah für geschützt erklärt hat. Ihre bösen Taten sind ihnen ausgeschmückt worden. Allah leitet das ungläubige Volk nicht recht.

Quran 9, 36 – 37. Übersetzt von: Abdullah As-Samit (F. Bubenheim) und Nadeem Elyas. Empfohlene Quellenangabe: Mit Allahs Hilfe ist diese Auflage des Qur'an mit der Übersetzung seiner Bedeutungen vom König-Fahd-Komplex zum Druck vom Qur'an in al-Madina al-Munauwara unter Aufsicht des Ministeriums für Islamische Angelegenheiten, Stiftungen, Da-Wa und Rechtweisung im Königreich Saudi-Arabien herausgegeben worden. 1424 n.H./2003 n.Chr. (2. Auflage). Online abrufbar unter URL: www.islam.de (20.10.2015).

Der Nasī’ (wörtlich “Aufschub”) ist eine Praxis des vor-islamischen Kalenders, deren genaue Inhalte unbekannt sind. Der erste, vom muslimischen Astronomen Al-Biruni entwickelte Erklärungsansatz interpretierte dieses Element als einen Schaltmonat. Ihm zufolge war der vor-islamische Kalender ein Mondkalender, ehe er durch Hinzufügung eines Schaltmonats zu einem Lunisolarkalender wurde, wobei der zweite Monat sich auf den dritten Monat usw. verschob. Einem anderen Erklärungsansatz zufolge handelte es sich um einen reinen Mondkalender, bei dem sich allerdings der Zeitpunkt einiger Feste verschob, damit sie immer in derselben Saison gefeiert werden konnten. Allen Interpretationen ist jedoch gemeinsam, dass der Nasī’ die Abgrenzung zwischen den heiligen und den übrigen Monaten verwischte.

Die Geschichte von Abrahams Opfer

99 Er sagte: „Gewiß, ich gehe zu meinem Herrn; Er wird mich rechtleiten. 100 Mein Herr, schenke mir einen von den Rechtschaffenen.“

101 Da verkündeten Wir ihm einen nachsichtigen Jungen.

102 Als dieser das Alter erreichte, daß er mit ihm laufen konnte, sagte er: „O mein lieber Sohn, ich sehe im Schlaf, daß ich dich schlachte. Schau jetzt, was du (dazu) meinst.“ Er sagte: „O mein lieber Vater, tu, was dir befohlen wird. Du wirst mich, wenn Allah will, als einen der Standhaften finden.“

103 Als sie sich beide ergeben gezeigt hatten und er ihn auf die Seite der Stirn niedergeworfen hatte, 104 riefen Wir ihm zu: „O Ibrāhīm, 105 du hast das Traumgesicht bereits wahr gemacht.“ Gewiß, so vergelten Wir den Gutes Tuenden. 106 Das ist wahrlich die deutliche Prüfung.

107 Und Wir lösten ihn mit einem großartigen Schlachtopfer aus. 108 Und Wir ließen für ihn (den Ruf) unter den späteren (Geschlechtern lauten): 109 109 „Friede sei auf Ibrāhīm!“ 110 So vergelten Wir den Gutes Tuenden.

111 Er gehört ja zu Unseren gläubigen Dienern. 112 Und Wir verkündeten ihm Isḥāq als einen Propheten von den Rechtschaffenen. 113 Und Wir segneten ihn und Isḥāq. Unter ihrer Nachkommenschaft gibt es manche, die Gutes tun, und manche, die sich selbst offenkundig Unrecht zufügen.

114 Und Wir erwiesen bereits Mūsā und Hārūn eine Wohltat 115 und erretteten sie beide und ihr Volk aus der großen Trübsal. 116 Und Wir halfen ihnen, da waren sie es, die Sieger wurden.

Quran 37, 99 – 116. Übersetzt von: Abdullah As-Samit (F. Bubenheim) und Nadeem Elyas. Empfohlene Quellenangabe: Mit Allahs Hilfe ist diese Auflage des Qur'an mit der Übersetzung seiner Bedeutungen vom König-Fahd-Komplex zum Druck vom Qur'an in al-Madina al-Munauwara unter Aufsicht des Ministeriums für Islamische Angelegenheiten, Stiftungen, Da-Wa und Rechtweisung im Königreich Saudi-Arabien herausgegeben worden. 1424 n.H./2003 n.Chr. (2. Auflage). Online abrufbar unter URL: www.islam.de (20.10.2015).

Dieser Ausschnitt aus dem Koran stellt die islamische Version der Erzählung von der Opfergabe Abrahams dar. Diese eher knappe Darstellung wird durch die Tradition überhöht. Die „feierliche Opfergabe“ wird im biblischen Text als die Opferung eines Widders interpretiert, der Koran ist im Vergleich dazu jedoch weniger genau. Auch wenn die Darstellung den Namen des geopferten Sohnes nicht erwähnt, wird davon ausgegangen, dass es sich um Ismael handelt (Ismā'īl). Schon früh haben sich Islamgelehrte Gedanken über die wahre Identität des Sohnes gemacht und haben Ansätze entwickelt, die nicht immer in Übereinstimmung mit der Tradition standen: Je nachdem, wie der Zeitpunkt der Ereignisse bestimmt wird, stellt die Geburt Isaaks eine Belohnung für die Opfergabe Abrahams dar, die auch erst nach der Geschichte von der Opferung erwähnt wird. Die Tradition fügt der Darstellung außerdem eine wichtige Begebenheit hinzu: Satan (Shaytān) erscheint insgesamt drei Mal, um Abraham von seinem Vorhaben abzubringen. Der reagiert, in dem er Steine nach ihm wirft. Dieser Reaktion wird während der Pilgerreise nach Mekka gedacht.

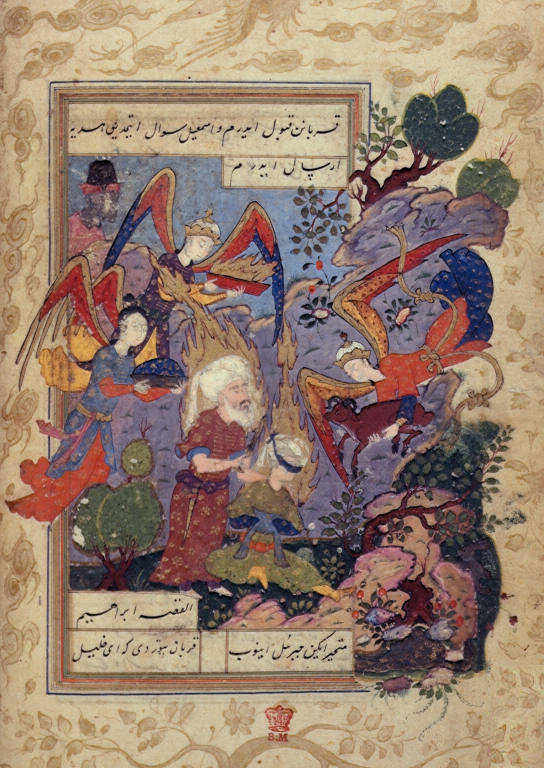

Das Opfer Abrahams

Französische Nationalbibliothek (Bibliothèque nationale de France), MS Arabe 1489, folio 5 verso

Wikimedia Commons Nutzung unter den Bedingungen der GNU-Lizenz für freie Dokumentation

Frei zugänglich.

Bild online abrufbar unter URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Offerismail.jpg

(30/03/2015)

Bei dieser Buchmalerei handelt es sich um einen Ausschnitt aus einem osmanischen Manuskript aus dem 16. oder 17. Jahrhundert. Er illustriert die wichtigsten Aspekte von Abrahams Opfergabe: Ismael wartet mit verbundenen Augen auf seine Opferung, während die Engel Abrahams Hand zurückhalten, da sie sich für eine alternative Opferform entschieden haben.