3. Judaism in the Middle and Modern Ages

When conversions to Christianity took place under the reign of Emperor Constantine, Jewish communities were dispersed in the entire Mediterranean basin and in other places, for example, in the lands that a few centuries later became the Carolingian Empire. In the Middle Ages, Jews were present in the two great religious and cultural spheres of Christianity and Islam. This expanded presence led to the emergence of multiple centres of Jewish civilization, including Eastern, Sephardic and Ashkenazi, and smaller communities with particular religious practices that are still in existence today.

Maimonides, The Guide for the Perplexed

The general object of the Law is twofold: the well-being of the soul, and the well-being of the body. The well-being of the soul is promoted by correct opinions communicated to the people according to their capacity. Some of these opinions are therefore imparted in a plain form, others allegorically: because certain opinions are in their plain form too strong for the capacity of the common people. The well-being of the body is established by a proper management of the relations in which we live one to another. This we can attain in two ways: first by removing all violence from our midst: that is to say, that we do not do every one as he pleases, desires, and is able to do; but every one of us does that which contributes towards the common welfare. Secondly, by teaching every one of us such good morals as must produce a good social state. Of these two objects, the one, the well-being of the soul, or the communication of correct opinions, comes undoubtedly first in rank, but the other, the well-being of the body, the government of the state, and the establishment of the best possible relations among men, is anterior in nature and time. The latter object is required first; it is also treated [in the Law] most carefully and most minutely, because the well-being of the soul can only be obtained after that of the body has been secured. For it has already been found that man has a double perfection: the first perfection is that of the body, and the second perfection is that of the soul. The first consists in the most healthy condition of his material relations, and this is only possible when man has all his wants supplied, as they arise; if he has his food, and other things needful for his body, e.g., shelter, bath, and the like. But one man alone cannot procure all this; it is impossible for a single man to obtain this comfort; it is only possible in society, since man, as is well known, is by nature social.

The second perfection of man consists in his becoming an actually intelligent being; i.e., he knows about the things in existence all that a person perfectly developed is capable of knowing. This second perfection certainly does not include any action or good conduct, but only knowledge, which is arrived at by speculation, or established by research.

It is clear that the second and superior kind of perfection can only be attained when the first perfection has been acquired; for a person that is suffering from great hunger, thirst, heat, or cold, cannot grasp an idea even if communicated by others, much less can he arrive at it by his own reasoning. But when a person is in possession of the first perfection, then he may possibly acquire the second perfection, which is undoubtedly of a superior kind, and is alone the source of eternal life. The true Law, which as we said is one, and beside which there is no other Law, viz., the Law of our teacher Moses, has for its purpose to give us the twofold perfection.

Mosheh Ben Maimon (Maimonides), Maimonides, The Guide for the Perplexed; III, 27. Trans. M. Friedländer.

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Guide_for_the_Perplexed_%281904%29

(09/02/2015)

This text is an excerpt from The Guide for the Perplexed (Moreh Nevuchim), the most important work by Moses Maimonides (1135-1204). He was a very influential Andalusian doctor, philosopher and jurist during his time, but also for many centuries afterwards, in the Jewish and non-Jewish world. His most important work, written in Arabic, connected the values, teachings and commentaries of Jewish law with Aristotelian philosophy, and added a philosophical and rational perspective on the holy writings. Based on Aristotelian logic and his views that divine revelation remained the highest form of truth, Maimonides attempted to shed light on the latter through allegorical interpretations. According to Maimonides, God can be perceived only through his accomplishments.

The excerpt included here is taken from the third and last volume of The Guide for the Perplexed and extols Jewish law, the Law of Moses, which gives men the opportunity to achieve a perfect soul and body. This text is a very good illustration of Maimonides’ method and intention to shed light on the biblical texts through philosophy.

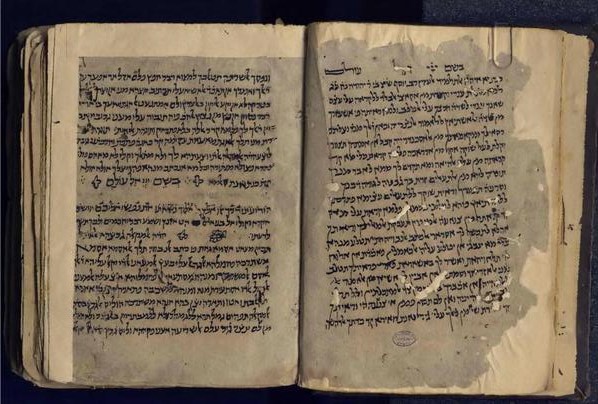

Manuscript from The Guide for the Perplexed

This picture is an excerpt from the manuscript of The Guide for the Perplexed, the most important work of Maimonides first published in 1190. The text presented here was published between 1200 and 1400 and written in Hebrew. It comes from the collection of the National Library in Israel.

Manuscript from The Guide for the Perplexed by Maimonides, dating between 1200 and 1400, National Library of Israel

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of the

GNU Free Documentation License:.

Public domain Image under URL:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Guide_to_the_Perplexed_WDL3963.pdf (09/02/2015)

French postal stamp showing the figure of Rachi of Troyes

This is a French postal stamp from the 2000s showing Rachi of Troyes, an exemplary figure in the Jewish world and beyond, from the medieval period in France. Rachi (1040-1105) was a rabbi, an exegetist, a jurist, but also a poet and a winegrower who lived in Troyes; he also wrote a large number of biblical and Talmudic commentaries. A great Jewish figure, he was also a notable intermediary figure since his work and thought had a considerable influence on Christian exegesis at the end of the Middle Ages. His influence on Jewish and western thought was such that it raised a great deal of continued interest in his work through the centuries, as illustrated by this postal stamp emphasizing his importance and contribution to the city of Troyes and to French and European culture.

Public domain Image under URL :

http://zakhor-online.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Timbre-Rachi-de-Troyes-20051.jpg

Exterior view of the Old-New synagogue, Prague

This is a photograph showing the façade of the Old-New synagogue in Prague. Located in the old Jewish quarter it is the oldest working synagogue in Europe. Built in the 13th century, it offers one of the most important examples of Gothic architecture in the Czech capital. During its construction, the architects, because of the laws at the time, ensured that the height of the synagogue did not go above the height of the churches in the city. It was first called New and then as of the 16th century, when other synagogues were built, it was called the Old-New Synagogue. The exterior of the synagogue is very sober. The interior includes a large hall for worship, divided into two naves, which are separated by pillars, next to which is the women’s area. The decoration inside is very ornate. It is the main place of worship of the Jewish community in Prague.

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution – Share alike 3.0 :

Image under URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old-New_Synagogue,_Prague_-_8283.jpg

(09/02/2015)

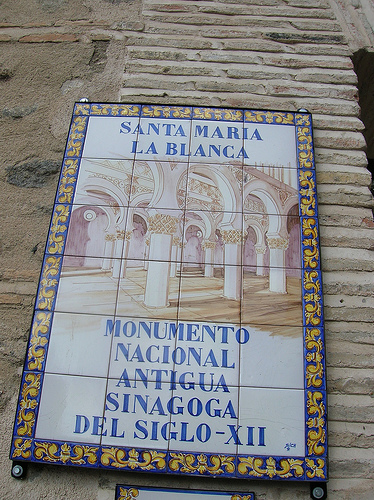

Santa Maria la Blanca synagogue, Toledo, commemorative plaque

This is a commemorative plaque from the building. The inscription on the plaque says that the building was originally a synagogue, built in the 12th century, before it was converted to a church, after the 14th century pogroms in Spain. The building today is a museum and a property of the Catholic Church.

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution – Commons Attribution 2.0:

Image under URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santa_Maria_la_Blanca.jpg

(09/02/2015)

Santa Maria la Blanca synagogue, Toledo, interior view

This is a photograph showing the interior of the Santa Maria la Blanca synagogue in Toledo. Erected in 1180, when the city was under Christian rule, the building was originally a synagogue in the Mudejar style. It was the main place of worship for the Jews of Toledo until the middle of the 14th century, and was converted to a church in 1405, after the pogroms, which had a huge impact on the community of the city. It became the Church of Santa Maria la Blanca and today it is a museum. The interior of the building is made up of white walls with decorative geometric motifs on the friezes and vegetal motifs on the capitals.

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License.

Public domain

Image under URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sinagoga_de_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca.jpg

(09/02/2015)