2. The major Christian festivals

The Christian calendar is based on the Roman calendar. It determines the dates of Christian celebrations, organised in different cycles around a central celebration. The rhythm of celebrations is the same in all Christian churches, but their exact date may vary. From early on, the astronomical calculation was an important element in the development of the Christian calendar, because it determined the date of Easter, around which all the movable celebrations were organized. Although the civil calendar derives from the Christian calendar, the liturgical year - which organizes the cycles of celebrations - does not match the calendar year. In the Catholic and Protestant Churches, the liturgical cycle begins with Advent (from the Latin adventus, meaning “arrival” or “advent”). In the Orthodox and Oriental Churches, it starts on September 1st, which was the first day of the calendar year in the Byzantine Empire.

A manger scene

Photo from a private collection

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

.

A manger (a term derived from a French word) scene is a figurative representation of the Nativity with the Child Jesus and the Holy Family, often associated with the ox and the ass (in reference to apocryphal traditions), or with the shepherds (in reference to the Gospel of Luke 2:8-16) and the Magi (in reference to the Gospel of Matthew 2:11). The first manger scenes were seen in churches in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In earlier times, Francis of Assisi participated in a live manger scene in 1223, inspired by devotional practices considering manger scenes as shows. The devotion to the manger scene has roots in the devotion to the Child Jesus, in the Franciscan spirituality, and in the Oratory Movement. It then spread in Baroque Europe with the Jesuits. In the nineteenth century, it took a more intimate and family dimension, while mixing it with popular and folk elements related to Christmas but unrelated to specific religious prescriptions. The manger scene gradually entered people’s homes, with smaller formats that were better suited to this new practice, for example the Santons of Provence (figurines produced in the Provence region of southeastern France), while churches were using life-size figurines. A miniature world with its trades and its picturesque scenes - and with the nativity scene being only one element of it - opened the way for secular and folk reappropriations, with a strong local identity in some regions.

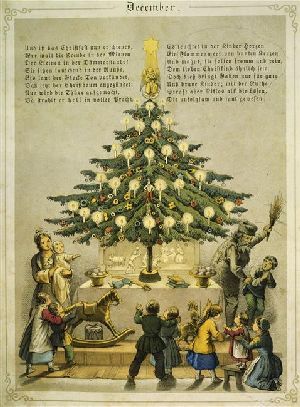

A Christmas tree

In the public domain.

The Christmas tree may have roots in former Celtic rituals around the winter solstice. In present times, its roots come from some religious rivalries during the Reformation, as a popular tradition unrelated to dogmatic prescriptions, like the manger scene. The Protestants considered that the manger scene, with its figurative representations, was too close to a worship of images or to a drift toward superstitions. For them, the tree of Paradise offered a more symbolic interpretation as a tree (often a spruce in eastern France) adorned with red apples. This tree was present in the medieval mystery plays around the Nativity. In the sixteenth century, people from Alsace (in eastern France) began putting this tree of Eden inside their homes, and decorating it with red balls before adding small white cakes as symbols of communion wafers, and candles as symbols of Christ, the new Adam, Light of the World. In the nineteenth century, this custom spread to Catholics, who put the Christmas tree beside the manger scene. Later on, the Christmas tree got secularized. With a weaker religious symbolism than that of the manger scene, it now goes beyond Christian circles as the center of a popular feast intended for all.

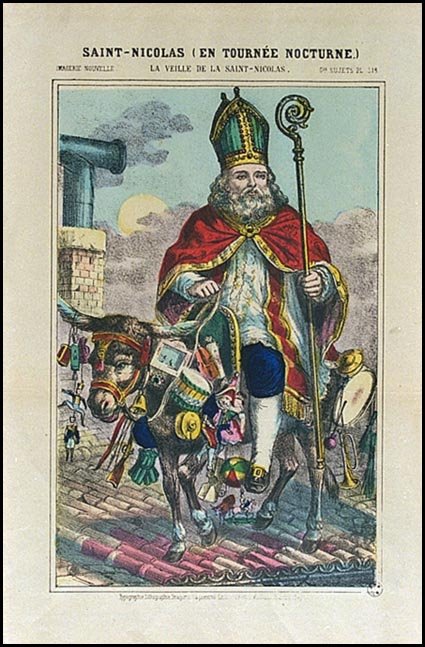

Saint Nicholas’ visits at night

In many ways, the tradition linked to Saint Nicholas has evolved alongside the tradition of the Christmas tree. Saint Nicolas, celebrated on December 6, was an important figure in Belgium, in the Germanic world and in the Anglo-Saxon countries. As the holy Bishop of Myra, Anatolia, and the protector of children, he was the popular Christianised version of pagan figures distributing gifts to children in the middle of winter, for example the Julenisse (Christmas elf). From the sixteenth century onwards, Saint Nicholas coexisted with other donor figures related to December 25, for example Christmas Snowman in France, Father Christmas in England, and Weihnachtsmann in Germany. Meanwhile, under the influence of the Reformation, the figure of Saint Nicholas got secularized. He became Sinter Klaas in the Netherlands, and arrived on the American continent through the Dutch colony of Nieuwe Amsterdam (that became New York). An American poem from 1823 named "A visit from Saint Nicholas" included most elements of the modern Father Christmas. Saint Nicholas had lost his ecclesiastical attributes (miter and crosier) but he had kept his white beard and his red clothes; he had traded his donkey against a sleigh pulled by eight reindeer; his task was now to come and distribute gifts on Christmas eve. In the mid-nineteenth century, American and British popular newspapers helped to disseminate the figure of Santa Claus in their illustrations, while linking it to Christmas. In 1931, the popular character became part of Coca-Cola’s advertising, which contributed to further disseminate this figure. Some Catholics have considered the popularity of Father Christmas as a “competition” against the Nativity in its religious sense. But the popular Christmas figure has now been secularized as a main character in a feast intended for children.

Image of Epinal

In the public domain

The Resurrection

3 For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, 4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Cephas [Peter], and then to the Twelve. 6 After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time […] 17 And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins.

1 Co. 15, 3-6 ; 17.

The First Epistle to the Corinthians includes the oldest reference to the Resurrection of Jesus, and its meaning for the still young Christian community of the time. In the excerpt below, the first verses will later be included in the Creed.

Procession of the Holy Week in Salamanca, Spain

In Spain, the Holy Week (the week before Easter) includes processions organized by brotherhoods, some of them dating back from the Middle Ages. These processions are an act of penance. The brothers are dressed with the nazareno, a penitential dress with a conical hood in some cases. They carry pasos, meaning a statue or a group of statues depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, a saint or a specific episode related to the Holy Week.

Wikimedia Commons,

Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License

Licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 unported

Image under the URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Semana_Santa_10.JPG

(30/03/2015)

The Dormition of the Virgin Mary

On August 15, the Orthodox and Oriental Churches celebrate the Dormition of the Virgin Mary. The word "Dormition" refers to a peaceful death, and can be used for saints who have not been martyred. In the case of the Virgin Mary, according to the tradition, she died peacefully, her soul (represented as a miniature Virgin Mary) was welcomed at once by Christ, and she resurrected before ascending to Heaven.

Ivory plate made in Constantinople in the late tenth or early eleventh century. Musée national du Moyen Âge (National Museum of the Middle Ages), France

Wikimedia Commons, Usable under the conditions of the

GNU Free Documentation License

Public domain. Image under the URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dormition_de_la_Vierge.JPG

(30/03/2015)

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary

In the Catholic Church, August 15 is the date for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The Catholic tradition does not really address the question of her death. The term "assumption" refers to the idea that she was "lifted off" to ascend to Heaven in flesh and soul, unlike other human beings who must wait until the end of times to know the resurrection of the flesh. In 1950, Pius XII (pope from 1939 to 1958) decided that the Assumption would become a dogma of the Catholic Church.

Painting by Michel Sittow (1449-1525), from the National Gallery of Art

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License

Public domain. Image under the URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ascension_of_the_virgin_Michel_Sittow.jpg

(30/03/2015)