3. The major Muslim festivals

The Islamic calendar - or Hijri calendar - is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months each lasting 29 or 30 days. This calendar is marked by several unique features, such as lacking a leap day or month, and deciding about the beginning of the month when the moon can be seen, instead of doing some astronomical calculations. The calendar is used by Muslims to decide about the precise time for Muslim celebrations, especially for the month of fasting (Ramadan) and the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj). In the Muslim world, this calendar is also used to date historical events, sometimes in parallel with the Gregorian calendar. Four of these months are sacred; during that time Muslims must not commit sins and take military action, except against the infidels. The first year of the Muslim calendar is equivalent to the year 622 of the Christian era, and corresponds to the Hegira, i.e. the departure of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina.

Muhammad prohibits the Nasī’

This illuminated manuscript is an excerpt from the seventeenth-century copy of the fourteenth-century manuscript of The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries (Kitāb al-āthār al-bāqiyah ‘an al-qurūn al-khāliyah) by Al-Biruni (973-1048). The book is a comparison of calendars from different civilizations, with some additional input relating to mathematics, astronomy and history. The image refers to an important time for the design of the Muslim calendar: the prohibition of the Nasī’.

French National Library (Bibliothèque nationale de France), MS Arabe 1489, folio 5 verso

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License

Public domain. Image under the URL http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maome.jpg

(30/03/2015)

The criticism of the Nasī’

36 Indeed, the number of months with Allah is twelve months in the register of Allah from the day He created the heavens and the earth; of these, four are sacred. That is the correct religion, so do not wrong yourselves during them. And fight against the disbelievers collectively as they fight against you collectively. And know that Allah is with the righteous who fear Him.

37 Indeed, the Nasī’ is an increase in disbelief by which those who have disbelieved are led further astray. They make it lawful one year and unlawful another year to correspond to the number made unlawful by Allah and thus make lawful what Allah has made unlawful. Made pleasing to them is the evil of their deeds; and Allah does not guide the disbelieving people.

The Quran, 9:36-37

The Nasī’ (literally “postponment”) is a practice of the pre-Islamic calendar, the exact terms of which are unclear. The first interpretation offered by Muslim astronomers like Al-Biruni considered it as a leap month. According to them, the pre-Islamic lunar calendar was only lunar before becoming a lunisolar calendar by adding a leap month, with the second month becoming the third month, and so on. According to another interpretation, this calendar was only lunar, but there was a shift for some celebrations, for them to occur during the same season. In all interpretations, the Nasī’ blurred the difference between the sacred months and other months.

The story of the sacrifice of Abraham

99 And [Abraham] said, "Indeed, I will go to my Lord; He will guide me. 100 My Lord, grant me a child from among the righteous."

101 So we gave him good tidings of a forbearing boy.

102 And when he reached with him the age of exertion, he said, "O my son, indeed I have seen in a dream that I must sacrifice you, so see what you think." He said, "O my father, do as you are commanded. You will find me, if Allah wills, of the steadfast."

103 And when they had both submitted and he put him down upon his forehead, 104 We called to him, "O Abraham, 105 You have fulfilled the vision." Indeed, We thus reward the doers of good. 106 Indeed, this was the clear trial.”

107 And we ransomed him with a great sacrifice. 108 And we left for him favorable mention among later generations: 109 "Peace upon Abraham." 110 Indeed, we thus reward the doers of good.

111 Indeed, he was of our believing servants. 112 And we gave him good tidings of Isaac, a prophet from among the righteous. 113 And we blessed him and Isaac. But among their descendants is the doer of good and the clearly unjust to himself.

114 And we did certainly confer favor upon Moses and Aaron. 115 And we saved them and their people from the great affliction, 116 And we supported them so it was they who overcame.

The Quran, 37:99-116

This excerpt from the Quran is the Muslim version of the sacrifice of Abraham (Ibrāhīm). This rather succinct account is magnified by the tradition. The “solemn sacrifice” is interpreted as that of a ram in the biblical text, but the Quranic text is not as precise. The name of the sacrificed son, though not mentioned in the account, is supposed to be Ishmael (Ismā'īl). Early on, Muslims scholars wondered about the true identity of the son, and have not always agreed with the tradition: depending on the timing of events, the birth of Isaac is a reward for the sacrifice of Abraham, but it is mentioned just after the story of the sacrifice. The tradition also adds an important episode: Satan (Shaytān) comes three times to try to dissuade Abraham, who answers back by throwing stones at him, a gesture which is commemorated during the pilgrimage to Mecca.

The sacrifice of Abraham

French National Library (Bibliothèque nationale de France), MS Arabe 1489, folio 5 verso

Wikimedia Commons Usable under the conditions of the GNU Free Documentation License

Public domain.

Image under the URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Offerismail.jpg

(30/03/2015)

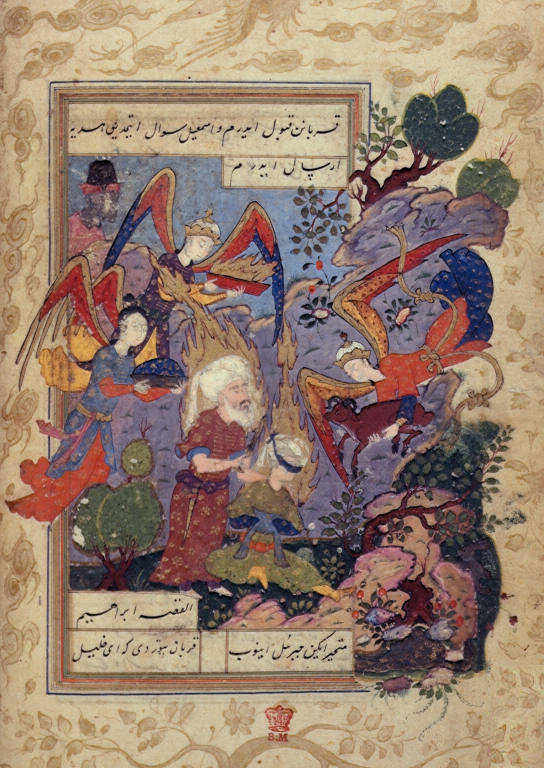

This illuminated manuscript is an excerpt from an Ottoman manuscript from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. It illustrates the most important points in the sacrifice of Abraham: a blindfolded Ishmael waiting to be sacrificed, and the angels stopping Abraham's hand and deciding for a replacement sacrifice.