4. Cultural exchanges

Through their turbulent history, Spain and Sicily became areas where diverse cultures coexisted. This contact generated conflict and cultural exchanges, giving the Christian world the opportunity to retrieve ancient Greek knowledge and wisdom.

The Life of Gerard of Cremona

The lamp which shines should not be set aside nor put under a bushel, but on a candlestick*; in the same way, the great works of man should not be buried in the stupor of silence but brought to the attention of people now because they open the door of virtue to future generations and bring to the attention of those present, by a worthy commemoration, examples of the Ancients as models of how one should live.

Thus, in order to ensure that a dark silence would not obscure Master Gerard of Cremona, that he would not be deprived of the benefit of his renown which he has earned, to ensure that a brazen theft would not allow anyone else to put their name to the works which he has translated, all the more so as he never accused anyone of this, his companions systematically drew up a list of all the works which he had translated, in the field of dialectics as well as of geometry, of astrology as well as of philosophy, of medicine as well as of the other sciences, by putting this list at the end of this Tegni, which he has just translated, imitating the way in which Galen lists all his works at the end of the same publication […].

Raised from birth, in the bosom of philosophy and having achieved the highest level of knowledge of all aspects available to him by studying the Latin peoples, the love of the Almagest, which he did not find in the Latin language, sent him to Toledo. There he saw a huge number of works in Arabic, covering all disciplines and deplored the absence of works on these subjects. He learned Arabic in order to be able to translate them; relying both on his knowledge of science and on his knowledge of language […], he translated from Arabic in the manner of the wise man who, running through the green meadows, does not pick all the flowers but only the most beautiful, in order to braid them into a coronet. And thus, until the end of his life, he never stopped translating, as clearly and carefully as he could, all the books which he judged to be the finest, in all the major disciplines, in order to make them available to the people of the Latin languages, as if to a beloved heiress.

*Matthew 5:15

The Life of Gerard of Cremona. Olivier Guyojeannin, Archives de l’Occident, t. I, Le Moyen Âge, Paris, 1992.

The Life of Gerard of Cremona is an anonymous text that can be found in various manuscripts from Gerard’s translation of Galen’s Tegni. It was written by one or many disciplines of Gerard who wanted to show the importance of his work as a translator. Gerard of Cremona (1114 – 1187) was one of the most prolific and important translators of his time. The works cited in the text are very important. Almageste is a monumental work on astronomy by Claude Ptolemeus (90 – 168). His name comes from the Arabic al-majistī, which is a distortion of the Greek title of the book, Hē megálē sýntaxis (The Great Treatise). Tegni, a distortion from the Greek Téchnē (art) is a book introducing the work of Galen, a doctor (129 – 216) who had considerable influence on Arab-Muslim and European medicine.

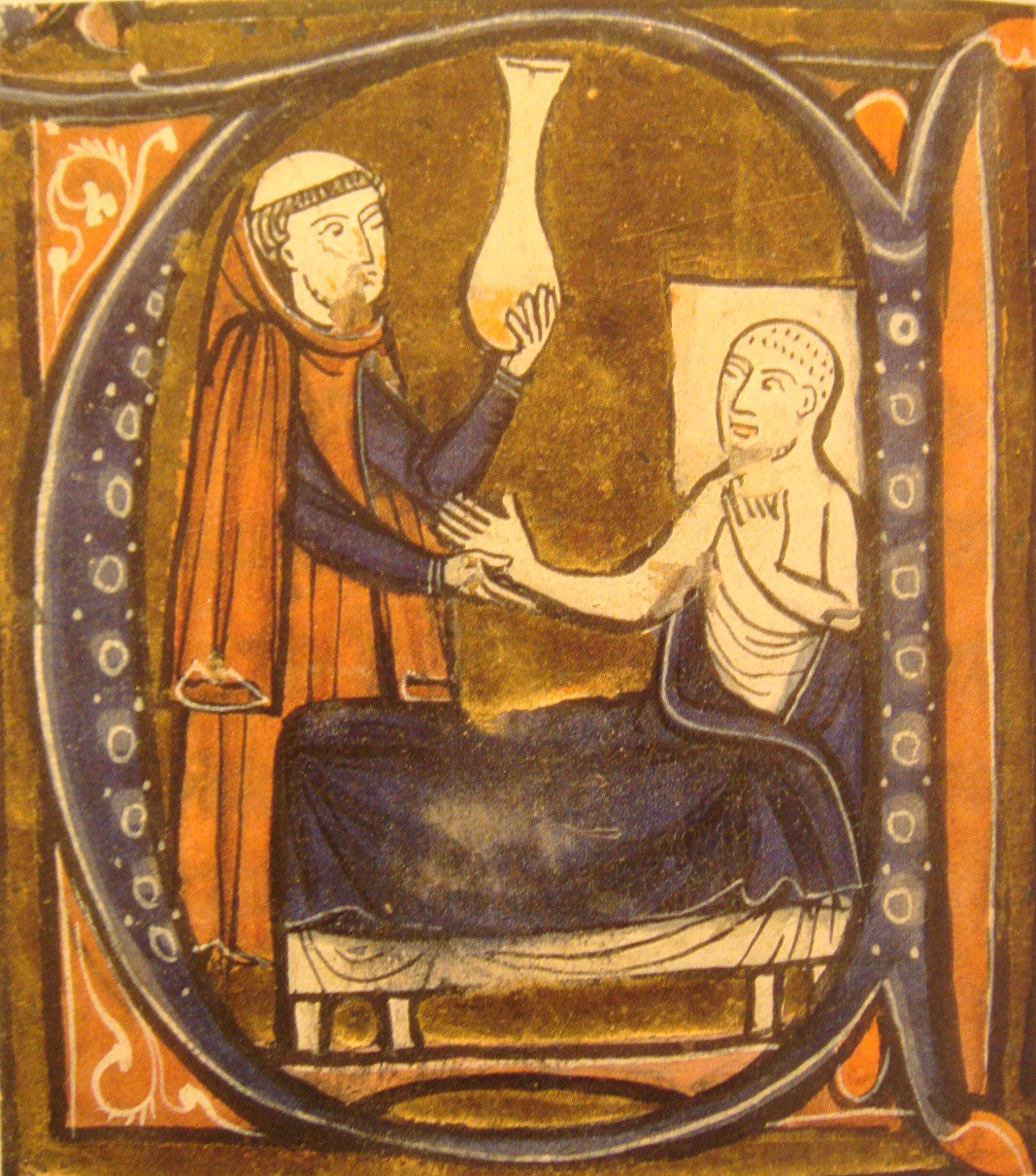

Portrait of Al-Rāzī from a Latin manuscript

Muhammad ibn Zakariyā al-Rāzī (Rhazes or Rasis, his name in Latin) (854 – 932 or 925) was a Persian doctor who defended the use of the scientific approach in diagnosis and treatment. He was the author of an important number of works. The image is from the manuscript of medical treaties translated between 1250 and 1260 by Gerard of Cremona. Rhazes holds a matula (a container to collect urine). Urine analysis was a common diagnostic method and was borrowed from Arab-Muslim medicine.

Wikimedia Commons. Usable under the conditions of

the GNU Free Documentation License

Public domain

Image under URL:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Al-RaziInGerardusCremonensis1250.JPG

(30/03/2015)

Preface by Peter the Venerable of the translation of the Quran

Whether one ascribes to the Islamic error the despicable name of heresy or the infamous one of paganism, it is necessary to act against it, in other words, to write. But the people of the Latin languages and especially the modern ones, the ancient culture having perished, following the word of the Jews who used to admire the polyglot* apostles, know no other language than that of the country of their birth. Thus they were not able to recognize the enormity of this mistake nor block its path. And so my heart was set aflame and a fire burned in me in my meditation. I became indignant at seeing how the Latin peoples appeared ignorant of the cause of this perdition and seeing how their mistake deprived them of the ability to resist it: because no one responded, because no one knew.

And so I went looking for specialists in the language, Arabic, that had allowed this deadly poison to infest more half the globe. I persuaded them, with prayers and money, to translate the history and the doctrine of this unhappy being and his law, which is called the Quran, from Arabic to Latin. And so as to ensure that the translation was complete and that no errors would distort our full understanding, I also added a Muslim to the team of Christian translators. Here are the names of the Christian translators: Robert of Ketton, Hermann the Dalmatian, Peter of Toledo; the Muslim was called Mohammed. This team, after scouring through the libraries of this barbarous people produced a huge book which they published for Latin readers.

This work was done in the year that I went to Spain and where I had an audience with Lord Alfonso, the victorious Emperor of all Spain, in the year of our Lord, 1142.

*Reference to Pentecost or Whitsun, the day when the apostles were given the gift of tongues and were able to speak all the languages of the world.

Jacques Le Goff, Les intellectuels au Moyen Âge, Paris, 1957.

Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete (Law of Muhammad the false prophet) was the first translation of the Quran in the West, where it was circulated until the 18th century. It was the first translation of the Quran into a European language. The translation was commissioned by Peter the Venerable, Abbey of Cluny from 1122 to 1156. He called on Robert of Ketton, one of the most reputable translators of his time, even if he is was known mostly for his scientific translations. The translation was commissioned in 1142 and completed in 1143. Even if, for a long time it was the only translation available in the West, this version was strongly criticized for having merely loosely paraphrased the original text.