2. Rabbinsk jødedom

Til trods for templets ødelæggelse og den periode af sorg, som fulgte, var jødernes liv fokuseret mod bøn og lærdom. I perioden fra 100-tallet til 300-tallet strukturerede den rabbinske jødedom sig progressivt. Som arvtager til en lang religiøs og kulturel tradition efterfulgte rabbinsk jødedom den farisæiske jødedom og etablerede mange af de stadigt gældende normer inden for jødedommen.

Triumftog, detalje fra Titusbuen, år 81, Rom

Denne triumfbue blev opført af den romerske Kejser Domitian i år 81 til minde om hans bror og forgænger Titus’ sejre i Judæa, især ødelæggelsen af Jerusalem og dens tempel i 70. Den her viste detalje fremstiller den romerske sejr. Siddende på en stridsvogn (quadriga) leder Titus et optog, som bærer på sejrsbyttet og er på vej ind gennem imperiets port. Byttet inkluderer en gylden syvarmet lysestage (menorah), et bibelsk symbol, der blev opbevaret i templet. Dette er den eneste visuelle fremstilling af lysestagen fra samtiden.

Triumftog, detalje fra Titusbuen, år 81, Rom

Wikimedia Commons. GNU Free Documentation License:.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

Billede hentet fra:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arch_of_Titus_Menorah.png (09/02/2015)

Dio Cassius Historia (’Roms Historie’), Liber LXVI:6, 1-3

Though a breach was made in the wall by means of engines, nevertheless, the capture of the place did not immediately follow even then. On the contrary, the defenders killed great numbers that tried to crowd through the opening, and they also set fire to some of the buildings near by, hoping thus to check the further progress of the Romans, even though they should gain possession of the wall. In this way they not only damaged the wall but at the same time unintentionally burned down the barrier around the sacred precinct, so that the entrance to the temple was now laid open to the Romans. 2 Nevertheless, the soldiers because of their superstition did not immediately rush in; but at last, under compulsion from Titus, they made their way inside. Then the Jews defended themselves much more vigorously than before, as if they had discovered a piece of rare good fortune in being able to fight near the temple and fall in its defence. The populace was stationed below in the court, the senators on the steps, and the priests in the sanctuary itself. 3 And though they were but a handful fighting against a far superior force, they were not conquered until a part of the temple was set on fire. Then they met death willingly, some throwing themselves on the swords of the Romans, some slaying one another, others taking their own lives, and still others leaping into the flames. And it seemed to everybody, and especially to them, that so far from being destruction, it was victory and salvation and happiness to them that they perished along with the temple.;

Dio Cassius Roman History, Book LXVI:6, 1-3

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/65*.html

(09/02/2015)

Dio Cassius var en romersk historiker, som levede i 100- og 200-tallet, og som skrev på græsk. Han blev født i Lilleasien og kom af en magtfuld og privilegeret familie. Han førte en karriere som fremtrædende embedsmand (cursus honorum) og var tæt på kejserne. Han er kendt for sit 80-bind værk Historia (’Roms Historie’), der fortæller Roms komplette historie fra begyndelsen til 229. Hans beretninger er ikke altid objektive, men de udgør en særdeles vigtig kilde til studiet af Roms historie. Uddraget inkluderet her omtaler Titus’ hærs’ ødelæggelse af Jerusalem i 70 og nedbrændingen af templet. Dio Cassius understreger jødernes modstand samt deres tilbøjelighed til at ofre samtidig med, at de forsvarede deres helligdom. Byen blev fuldstændig ødelagt, kun Davidstårnet og templets vestlige mur stod tilbage. Denne begivenhed, som tilendebragte fire års på hinanden følgende krige i kølvandet på det jødiske oprør mod Rom, blev også startskuddet til den anden jødiske diaspora. Den fik vigtige religiøse konsekvenser, der førte til ødelæggelsen af det vigtigste helligsted, og skabte en stor ideologisk og liturgisk udfordring for jøderne.

Tympanon fra Dura-Europos synagogen (2.-3. århundrede)

Dura-Europos synagogen, som i dag ligger i Syrien, var del af antikkens hellenistiske og romerske provins. Ifølge de oplysninger, vi har i dag, har bygningen været kendt siden 200-tallet, men der har formentlig ligget en tidligere bygning før den. Den blev opdaget i 1920 og fremstiller en række førhen ukendte billedfreskoer fra en ældgammel synagoge. De er nu en del af National Museum of Damaskus’ samlinger.

Dette er nichen i den hellige bue fra synagogens vestlige mur, der vender mod Jerusalem. Dens formål var at opbevare skriftrullerne med Toraen. Gavlpartiets midterstykke er dekoreret med en fremstilling af templet i Jerusalem, hvor Pagtens Ark befandt sig indtil dets ødelæggelse. Det kan ses som en visuel repræsentation af et ønske om at mindes den ødelagte helligdom, jødedommens uforgængelighed samt håbet om en national renæssance.

Til venstre for templet er der en syvarmet lysestage (menorah), et bibelsk symbol fra den hellige tekst i Moses’ Tabernakel, fra Salomons tempel. Den visuelle fremstilling af denne menorah er et gennemgående motiv i diasporaens synagoger. Der er også to andre symbolske jødiske elementer: en palmegren (lulav) og en citrusfrugt (etrog) – henvisninger til helligdagen sukkot (eller løvhyttefesten), en hentydning til indvielsen af Salomons tempel.

På den modsatte side, til højre for templet, findes en fremstilling af den bibelske fortælling om Abrahams ofring af Isak, som ifølge historien fandt sted på Moriabjerget. Dette er den ældste visuelle fremstilling af denne velkendte bibelfortælling. Abraham ses fra ryggen og med ansigtet mod alteret, hvorpå han fastholder sin søn Isak, mens han i sin højre hånd holder en kniv – klar til at foretage ofringen. Men Guds hånd i freskoens øverste del stopper Abrahams hånd. Nedenfor står en vædder bundet til et træ, som Abraham ikke kan se, og ovenfor er der et kegleformet telt og en lille figur, der – ifølge rabbinsk tolkning – forestiller Sara, sendt af Satan for at hjælpe til med at udføre ofringen.

Alle tre scener, der pryder gavlpartiet, hentyder til templet i Jerusalem.

Tympanon fra Dura-Europos synagogen (2.-3. århundrede)

Wikimedia Commons. Må anvendes i overensstemmelse med GNU Free Documentation License.

Public domain

Billede hentet fra: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dura_Synagogue_ciborium.jpg

(09/02/2015)

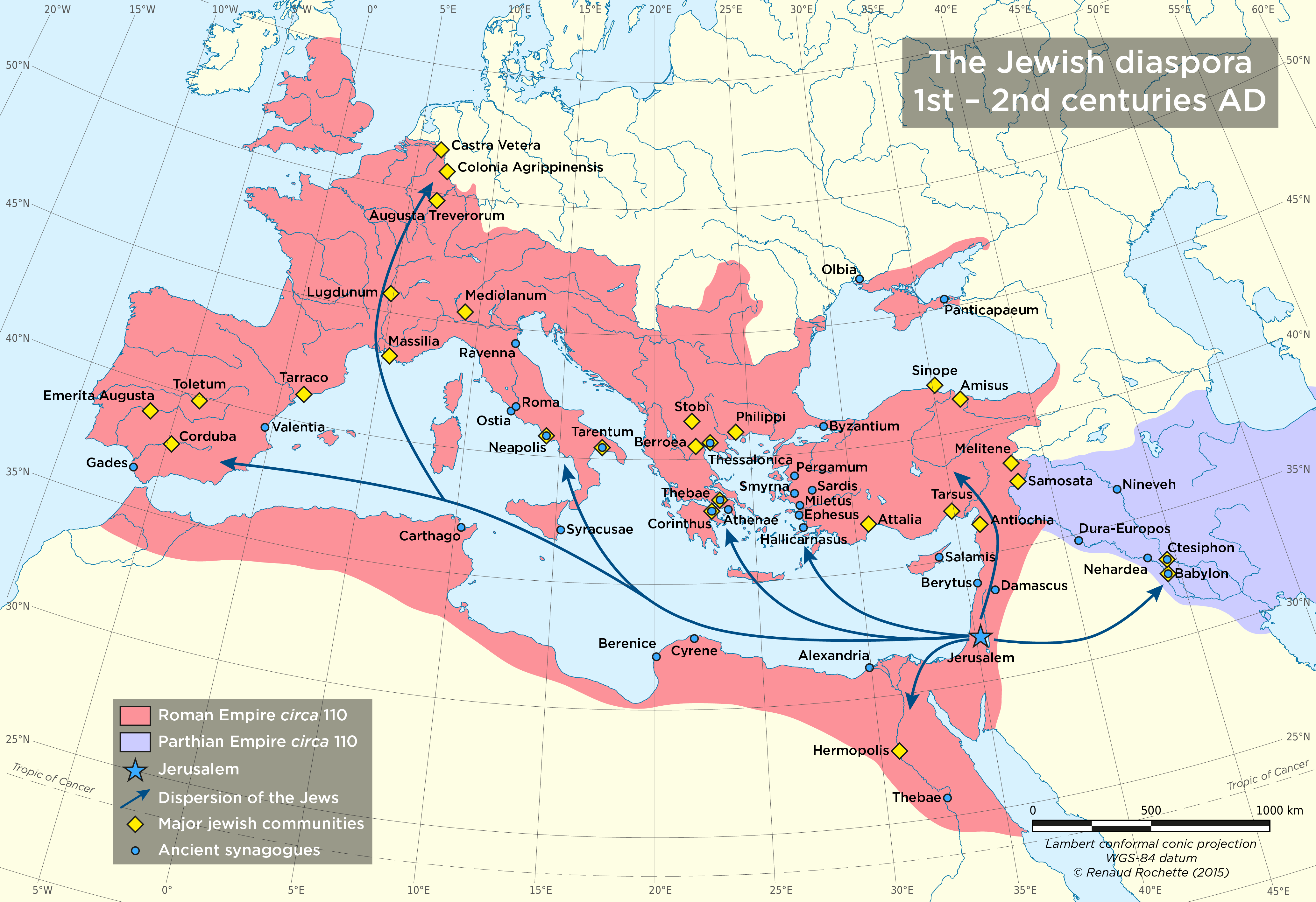

Den jødiske diaspora i det 1. og 2. århundrede

Den jødiske diaspora går forud for ødelæggelsen af templet i Jerusalem i 70, idet den dateres helt tilbage til det babylonske eksil og ødelæggelsen af det første tempel i 500-tallet f.v.t. Den anden jødiske diaspora hænger sammen med ødelæggelsen af Jerusalem og dens tempel såvel som med store bølger af jødiske udvandringer fra Palæstina og mod det romerske kejserrige. Men disse jøders separation fra deres åndelige centrum indebar ikke noget brud med deres religiøse tro og traditioner. Jødernes ”spredning” gav anledning til, at mange forskellige jødiske fællesskaber udviklede sig rundt om i verden, hvilket har medført en meget varieret jødisk kultur.

Forfatter: Renaud Rochette

Lambert conformal conic projection

Standard breddegrad: 20°N og 60°N

Standard længdegrad 20 °Ø

WGS-84 datum

Hydrografi (kystlinjer, søer og floder): NaturalEarth (public domain)

Data: http://www.naturalearthdata.com

Hydrography (coastline, lakes and rivers): NaturalEarth (public domain)

Tilladelse i kraft af Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International