6. Reformationstiden

Reformering af kirken har været en relativt udbredt ide siden afslutningen af det første årtusinde (se side 4 i dette modul) og udspringer af et ønske om at vende tilbage til en tilstand, der betragtes som mere oprindelig. Reformationen, en betegnelse der omslutter alle protestantiske reformer, og som også igangsatte en katolsk reformation (den såkaldte modreformation), adskiller sig fra tidligere bevægelser i sit omfang samt det faktum, at den ændrede Europas udseende.

Reformationen bør anskues i en større historisk sammenhæng. Efter middelalderen indledte den latinske kirke igen og igen reformer, der sigtede mod at korrigere praksisser, der ansås for at være fejlagtige, med henblik på en tilbagevenden til den oprindelige kirkes renhed. Den gregorianske reform (1000-tallet) er den bedst kendte, selv om den på ingen måde var den eneste. I 1300- og 1400-tallet befandt den vestlige kirke sig i en krise: den var spaltet på grund af det store skisma (med henføring til 1378-1417 [betegnelsen ”det store skisma” bruges også om øst-vest skismaet i 1054]), og blev samtidig udfordret af kritiske røster fra den engelske teolog John Wycliffe og præsten Jan Hus i Prag; begge kritiserede kirken på grund af dens store rigdom, dens tunge hierarki og dens brug af latin frem for folkesproget. Samtidig tog renæssancehumanismen fart, og den historisk-kritiske metode dukkede op sammen med humanismen og stillede ældre og bedre tekstversioner af originale værker, såsom Biblen, i forgrunden. Mange humanister råbte på en kirkereform, men kirken havde vanskeligt ved at føre dette ud i livet. Den protestantiske reformation fik sin styrke fra disse strømninger samtidig med, at den fandt støtte på det politiske plan.

.

Martin Luther: De 95 teser

De 95 teser, der efter sigende blev slået op på døren af kirken i Wittenberg den 31. oktober 1517, betragtes som startskuddet for den protestantiske reformation. Luther fordømte kirkens afladsbreve, men uden at stille sig fjendtligt an over for paven. De 95 teser affødte ikke desto mindre en omvæltning.

“Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and ordinary lecturer therein at Wittenberg, intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them in that place. Therefore he asks that those who cannot be present and dispute with him orally shall do so in their absence by letter. In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Amen.

1. When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ``Repent'' (Mt 4:17), he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

2. This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

3. Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortification of the flesh […].

5. The pope neither desires nor is able to remit any penalties except those imposed by his own authority or that of the canons.

6. The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring and showing that it has been remitted by God; or, to be sure, by remitting guilt in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in these cases were disregarded, the guilt would certainly remain unforgiven […].

20. Therefore the pope, when he uses the words “plenary remission of all penalties,'' does not actually mean ``all penalties,'' but only those imposed by himself […].

21. Thus those indulgence preachers are in error who say that a man is absolved from every penalty and saved by papal indulgences.

22. As a matter of fact, the pope remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to canon law, they should have paid in this life.

23. If remission of all penalties whatsoever could be granted to anyone at all, certainly it would be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to very few […].

27. They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory […].

28. It is certain that when money clinks in the money chest, greed and avarice can be increased; but when the church intercedes, the result is in the hands of God alone […].

32. Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

33. Men must especially be on guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to him.

34. For the graces of indulgences are concerned only with the penalties of sacramental satisfaction established by man.

35. They who teach that contrition is not necessary on the part of those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessional privileges preach unchristian doctrine.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

38. Nevertheless, papal remission and blessing are by no means to be disregarded, for they are, as I have said (Thesis 6), the proclamation of the divine remission […].

48. Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting indulgences, needs and thus desires their devout prayer more than their money.”

Martin Luther, The Ninety-Five Theses (1517). http://www.luther.de/en/95thesen.html

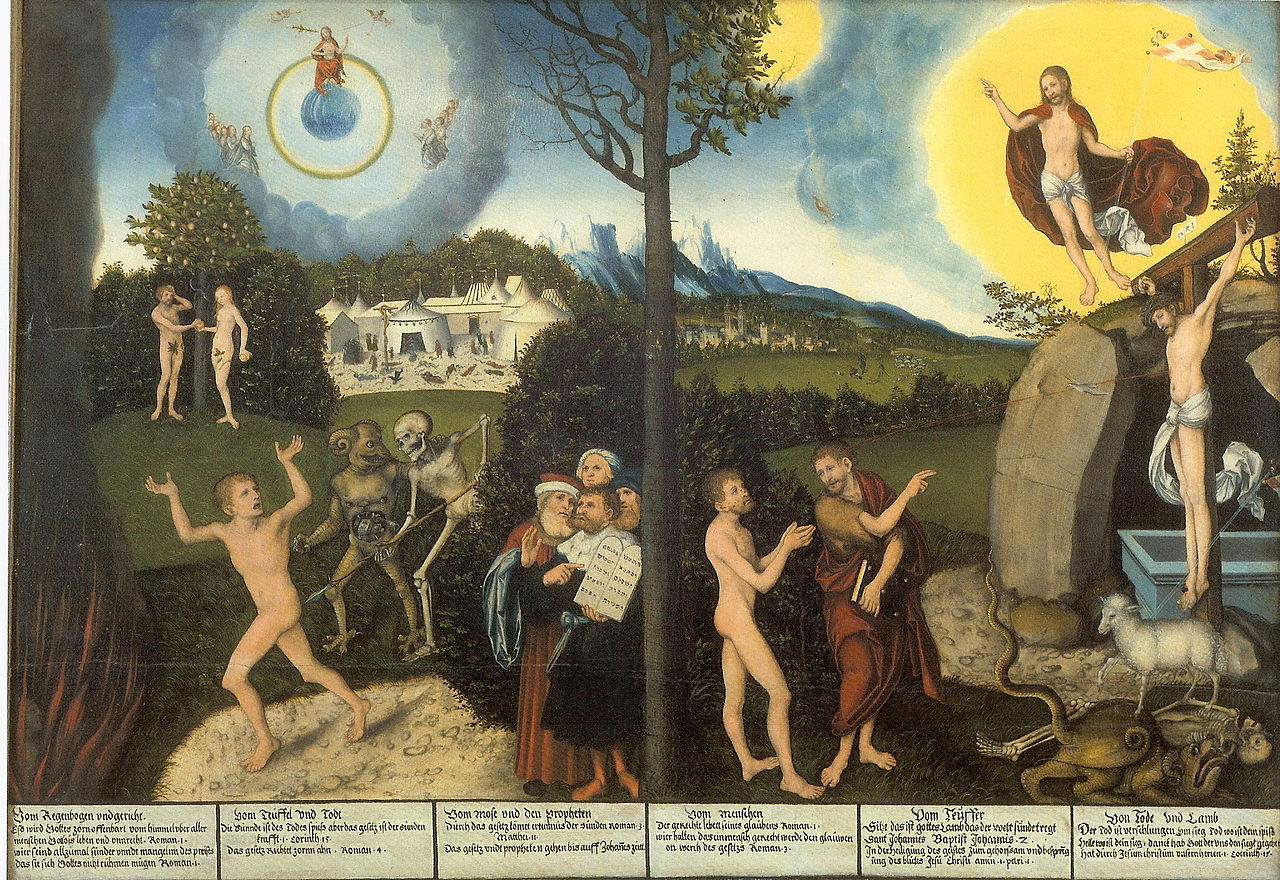

Lucas Cranach den ældre: Lov og nåde

Lucas Cranach den ældre (ca. 1472-1553) var en tysk maler. Han gjorde karriere som portrætkunstner og malede mange billeder af Martin Luther og hans familie. En anden side af hans arbejde var forbeholdt religiøse motiver. Lov og nåde kontrasterer Loven (dvs. det Gamle Testamente), der fordømmer syndere, med nåden (evangelierne), som frelser menneskene. Dette værk relaterer også til kontroverserne mellem katolikker og protestanter: katolikkerne insisterer på, at nåden opnås gennem gode gerninger, mens protestanterne holder på, at troen alene bringer frelse.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Law and Grace (1529). Gotha, Schlossmuseum Hentet fra: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cranach_Gesetz_und_Gnade_Gotha.jpg

Martin Luther: Den kristne frihed

Den kristne frihed er et af Luthers allervigtigste værker, da det fremstiller hans tese om et modsætningsforhold mellem gode gerninger, der intet har at gøre med frelse, og troen, som udgør den eneste vej til frelse.

“Let us examine the subject on a deeper and less simple principle. Man is composed of a twofold nature, a spiritual and a bodily. As regards the spiritual nature, which they name the soul, he is called the spiritual, inward, new man; as regards the bodily nature, which they name the flesh, he is called the fleshly, outward, old man. The Apostle speaks of this: “Though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day” (2 Cor. iv. 16). The result of this diversity is that in the Scriptures opposing statements are made concerning the same man, the fact being that in the same man these two men are opposed to one another; the flesh lusting against the spirit, and the spirit against the flesh (Gal. v. 17) […].One thing, and one alone, is necessary for life, justification, and Christian liberty; and that is the most holy word of God, the Gospel of Christ […].Meanwhile it is to be noted that the whole Scripture of God is divided into two parts: precepts and promises […].Now when a man has through the precepts been taught his own impotence, and become anxious by what means he may satisfy the law—for the law must be satisfied, so that no jot or tittle of it may pass away, otherwise he must be hopelessly condemned—then, being truly humbled and brought to nothing in his own eyes, he finds in himself no resource for justification and salvation. Then comes in that other part of Scripture, the promises of God […].For what is impossible for you by all the works of the law, which are many and yet useless, you shall fulfil in an easy and summary way through faith.”

Martin Luther, Concerning Christian Liberty, The Harvard Classics vol. 36.

Dekret om retfærdiggørelse (Tridentinerkoncilet)

Tridentinerkoncilet (1545-1563) var et økumenisk koncil, der blev afholdt i den italienske by Trento. Det var et af de vigtigste konciler for den romersk-katolske kirke. Det fordømte de protestantiske reformatorer og etablerede mulighederne for at bekæmpe deres ideer ved at forbedre kirkens formelle sammensætning. Koncilet blev starten på det, der i lang tid har været omtalt som modreformationen, men som i dag i stigende grad benævnes som den katolske reformation, siden de spørgsmål, koncilet satte sig for at løse, også relaterede til kirkens struktur.

Chapter 1: “[…] it is necessary that each one recognise and confess, that, whereas all men had lost their innocence in the prevarication of Adam-[…] they were so far the servants of sin […] although free will, attenuated as it was in its powers, and bent down, was by no means extinguished in them.”

Chapter 9: “But, although it is necessary to believe that sins are remitted […] gratuitously by the mercy of God for Christ's sake; yet […] [one cannot rely on the] certainty of the remission of his sins […].For even as no pious person ought to doubt of the mercy of God, of the merit of Christ, and of the virtue and efficacy of the sacraments […], no one can know […] that he has obtained the grace of God.”

Chapter 10: “Having, therefore, been thus justified, and made the friends and domestics of God, advancing from virtue to virtue, they are renewed, as the Apostle says, day by day; that is, by mortifying the members of their own flesh, and by presenting them as instruments of justice unto sanctification, they, through the observance of the commandments of God and of the Church, faith co-operating with good works, increase in that justice which they have received through the grace of Christ, and are still further justified […]. Do you see that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only.”

Council of Trent, Decree on Justification, 6th session (January 13, 1547), oversat af J. Waterworth.