For Islam, Jerusalem is the land of prodigies, the land of the prophets, the land where the Prophet’s Companions and religious scholars were buried. Jerusalem is also the heart of the holy land of Palestine, consecrated by a network of tombs (including those of Moses and Abraham), qubba-s (buildings with domes) and places of worship. Some prophets are worshiped in small shrines on the esplanade, near the famous monuments, but this memory has gradually left the Islamic imaginary. These monuments have suffered from the loss of memory, or have lost their identity, or they no longer constitute a strong impetus of faith. However, in the nineteenth century, conscientious Muslim pilgrims, together with their invaluable guides, searched the haram for the "birthplace of Jesus" and the mihrab of Zachariah and David.

The influence of Jerusalem, the holy city of Judaism and Christianity, preceded its sanctification by Islam. The holiness of Jerusalem was built slowly by drawing both from the traditions connecting Jerusalem to the life of Muhammad and the Jewish and Christian traditions.

The name of Jerusalem is absent from the Quran, which referred to it as "the far away Temple", an expression that connects it to the Jewish tradition. Its Roman and pagan name from the second century (Aelia transcribed as Iliya) was abandoned in favour of names referring to its holiness: Bayt al-Maqdis, Bayt al-Muqaddas, and then simply as al-Quds which indicates the city of Jerusalem but also to the Holy Land, the land of the prophets.

The famous hadith of "the three mosques" (late seventh/early eight century) ranked Jerusalem in the third place among the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

The holiness of Jerusalem was built on three fundamental elements:

Its position as a historic qibla [see module Islam II, page 8] by those who first "submitted" to God. The new community that settled in Yathrib turned toward Jerusalem to worship God. According to the Quran (2, 136) the Prophet changed the sacral direction of prayer. The hadiths date this change shortly after the hegira, when the qiblah was turned again toward Mecca.

Al-Quds as the horizon in the wait for the end of time.

The Prophet’s "journey" and his ascension constitute the essence/example/model[?] of the legendary destiny of Jerusalem.

Early Islam dreamed of Jerusalem even before the Arab conquest of Syria and Palestine. The founding text of the Muslim "dream" is the Quran. According to the interpretation, Jerusalem is named in the first verse of sura 17, as Al-isra' (the night journey): "Glory be to the One who took His servant by night from the Restricted Temple to the most distant temple which We had blessed around, so that We may show him of Our signs." The journey is linked to the "Noble Rock", the "Hanging Rock", and became the sacred place where the Prophet laid his head to pray, where there is a footprint before ascending to the heavens and the fingerprints of angel Gabriel, who wanted to keep the rock from following Muhammad in his ascension. In the Islamic literature, the Rock or "Noble rock" refers to the stone and the monument that sits on it. This stone is also associated with the Jewish tradition: it is the "Foundation Stone", the "foundation" with the "ligature" [?] and the construction of the Temple.

The image of Jerusalem has been enriched also with popular legends, magical stories and mystical references that are often found in the Jewish imaginary. As in the Jewish tradition, Jerusalem is the first land created by God. Close to paradise, it "brings together the benefits of this world and those of the world “beyond”. It is also the place of the transition of humanity to the end of time.

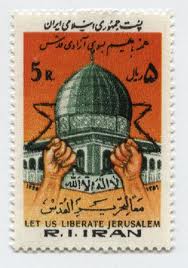

In Mandatory Palestine holy places were at the heart of the conflict between the Palestinian Arabs and Jews, who until then were considered in Ottoman Palestine as dhimmis (tolerated minorities with rights: see module Islam I, page 2). These tensions were connected to the strong Jewish migration and to the force of the Zionist movement. The settlement of Jews in Palestine changed the Arabic view of the Jewish community, which increasingly identified with the Zionist majority. Riots broke out in August 1929 during the renovation works near the wall undertaken by the Muslim authorities. The committee for the protection of Zionism saw in this effort the wish to disrupt Jewish celebrations at the foot of the wall (Kotel) for which it claimed ownership. The violence led to more than 100 deaths on each side.

In 1930 an international commission confirmed the property rights of the Muslim foundation on the al-Buraq wall, an integral part of the Mosque of al-Quds, as well as "the road along the border of the city wall called ‘the Maghreb quarter’", which overlooked the same wall. For Muslims this wall was sacred. As "a property of Islam" it symbolizes the struggle against Zionism.

Al-Quds was the city dreamed and inspired by Muslim mysticism and eschatology, a place of political and religious conflicts, and a place challenged by reconquest, "archaeological battles" and deadly clashes up to the esplanade itself[?]. Even today, the "wall", used by both communities, stands as a symbol of national unity. In 2001, a fatwa by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Ikrama Sa'id Sabri, proclaimed:

“The Al-Buraq wall is part of the wall of the Al-Aqsa mosque. Moreover, the Prophet Muhammad himself hallowed it when he attached to it (the mare) Al-Buraq, who had carried him on her back from Mecca to Jerusalem […]. hence we declare that this wall belongs to Islam and has nothing to do with Jews.”